Directed by: George Scribner

Written by: Jim Cox, Tim Disney and James Mangold

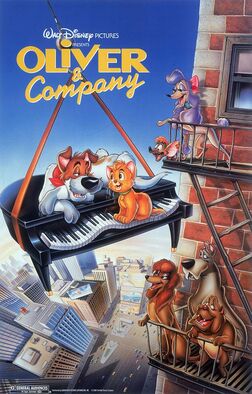

Despite being a recurring part of my childhood, Oliver and Company has not exactly become one of the Disney Classics. The film, which takes the story of Dickens’ Oliver Twist and makes it about a cat and some dogs living in contemporary (1980s) New York City, came out a year before Disney’s renaissance period started: a year before The Little Mermaid, etc. Rewatching the film as an adult, I was able to appreciate the ways in which it didn’t quite work, but also saw the inspiration it instilled in me as a child.

Despite being a recurring part of my childhood, Oliver and Company has not exactly become one of the Disney Classics. The film, which takes the story of Dickens’ Oliver Twist and makes it about a cat and some dogs living in contemporary (1980s) New York City, came out a year before Disney’s renaissance period started: a year before The Little Mermaid, etc. Rewatching the film as an adult, I was able to appreciate the ways in which it didn’t quite work, but also saw the inspiration it instilled in me as a child.

Oliver and Company opens with a song performed by the grizzly-voiced, new-wave singer Huey Lewis called “Once Upon a Time in New York City.” The screen zooms in on sunlit skyscrapers and then takes a tour through the city’s grand, increasingly melancholic streets. The film marks a stark break from Disney’s general approach of finding magic in the rural and unreal. As someone who was growing up in a big city (but one that wasn’t quite New York), Oliver and Company served as a rare example of a work that both brought my own surroundings to life, while nonetheless creating an “imaginary” world for me to dream of. This vivacity continues into the film’s other great song. “Why Should I Worry.” The city-rocker is sung by a dog named Dodger (Billy Joel: yes, that Billy Joel) as he teaches an unadopted kitten named Oliver (Joey Lawrence) how to procure food with “street savoir-faire.”

Oliver Twist, the film’s source material, may be the source of its problem. While I do not know the novel too well, its political legacy is a complex one. On the one hand, Charles Dickens is known for writing critically on the squalid conditions of Victorian England’s poor, a task Oliver Twist undoubtedly takes on. On the other hand, the novel would hardly pass for progressive today, both because one of its villains, Fagin, is a stereotyped-Jew, and also because Oliver is not saved by the mobilization of his fellow destitute, but instead by the charity of a rich man. Moral issues aside, this latter point may be what holds Oliver and Company back from having a fully satisfying story. Oliver does not have to be a hero himself, he only has to be saved. As a result, the film’s second half revolves around Oliver getting passed around while assorted decisive actions take place. There is no satisfying epiphany or decision on Oliver’s part, thus rendering him one of Disney’s least relevant title characters.

Musically, furthermore, the film does not quite hold up to the Disney movies that followed it. “Once Upon a Time in New York City,” is a great song, but its an introductory piece, not owned by a character. “Why Should I Worry,” is a classic, but a tad too short (though its reprise has to be one of my favorite, bittersweet movie moments). “Streets of Gold,” feels even shorter, as does the otherwise sweet and solid “Good Company.” Finally, “Perfect isn’t Easy,” sung by the arrogant poodle Georgette (Bette Middler) is visually wonderful, but lacks a real lyrical hook.

Oliver and Company may lack the musical structure or the narrative coherence to have become a classic, but its world building is still strong enough to make me smile, and was undoubtedly very compelling to my younger self. It not only brings out the “once upon a time,” in the city, but also brings together a rich set of characters. In addition to Oliver, the quasi-villainous Georgette, and the slick Dodger, there’s a whole gang of dogs including the wonderfully pretentious Francis (Roscoe Lee Brown), the adorably dopy Einstein (Richard Mulligan), the tough but protective Rita (Sheryl Lee Ralph/Ruth Pointer), and Tito the Chihuaha (Cheech Marin) (whose womanizing, Latin schtick, is admittedly the film’s most dated feature). The film’s humans are also endearing. Fagin (Dom DeLuise), a gentle, yet cartoonishly incompetent thief, is perhaps Disney’s warmest parent figure. This character clearly resonated with me, as when I first tried reading Oliver Twist years after watching this movie, I refused to accept that any version of Fagin could possibly be a villain.

Oliver and Company may lack the cultural conspicuousness of other Disney works. It is not an epic tale of a dream coming true, nor is it old or “pastoral” enough to be a classic. But for those looking for magic in their city, or for those who simply wished Dickens’ had written Fagin a little differently (perhaps Dickens himself is included on that list), the film can be just as much a treasurer as anything the Disney Renaissance has to offer.

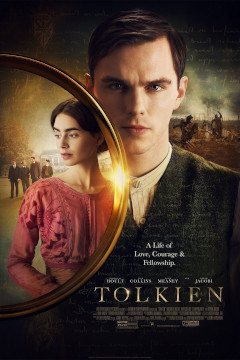

I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again. Biopics are often made based on the false presumption that the lives of interesting people make for interesting stories. A biopic without a premise beyond mere retelling will often disappoint. The writers of Tolkien at least had a sufficiently-developed premise in mind, but alas they weren’t bold enough in pursuing it.

I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again. Biopics are often made based on the false presumption that the lives of interesting people make for interesting stories. A biopic without a premise beyond mere retelling will often disappoint. The writers of Tolkien at least had a sufficiently-developed premise in mind, but alas they weren’t bold enough in pursuing it.