Best Actor in a Supporting Role

Sadly, the Oscars largely ignores non-English-language films outside of the best International Film category. As far as I’m concerned, that’s part of why the Oscars risk irrelevance. The awards already don’t cater to “average-Joe” movie goers, by ignoring blockbuster releases. By failing to pay attention to small-indie, and non-English films, the Academy also gives the middle-finger to people are actually invested in the cinematic art.

I would argue the year’s most compelling “supporting” performance came from French actor Vincent Lindoln. Julia Ducournau’s film Titane starts out as a surreal, Tarantino-esque gore-fest, based around leading actress Agathe Rousselle. Lindoln, plays the important role of turning the film’s tone on its head. He portrays a tough, middle-aged fire-fighter, whose sensitive side comes out when he’s made to believe his kidnapped son has been returned to him after ten years.

It would also be fun to have Don Cheadle given an Oscar nomination for his role in Space Jam 2. Cheadle’s character is an evil, personifed algorithm that tries to trap Lebron James in the internet. Space Jam 2 has a tragically mediocre script, but that doesn’t make Cheadle’s portrayal of a corny, yet sinister villain any less engaging. Talent can thrive in all kinds of contexts, and it’s a shame that The Academy doesn’t have the nuance to recognize that.

Best Actress in a Supporting Role

Yet another of my gripes with the Oscars is the narrow meanings of the categories “leading” and “supporting” role. The awards twist these words to (usually) mean “actor with the most lines/screen time” and “actor with slightly less screen time than the leading actor.” Thus, Brad Pitt won an Oscar as a “supporting actor” in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, despite being just as much the film’s protagonist as Leonardo DiCaprio.

Diana Rigg, does not enter Last Night in Soho with the bravado of a Brad Pitt. No. She enters the film as a character-actor, playing a well-defined, but seemingly insignificant landlady. Her character gradually takes on more importance in Edgar Wright’s film, but Rigg, who would die before the film was released, ensures that her character’s development is perfectly executed.

Best Actress in a Leading Role

Musician Alana Haim made her Hollywood-acting debut in Paul Thomas Anderson’s Licorice Pizza, and got to play a 25-year old character who struggles, to a fault, with immaturity (the most extreme manifestation of this being that she regularly hangs out with a 15-year old actor who is determined to make her his girlfriend).

While cinema has no shortage of immature figures, Haim’s character is unique. She’s not the kind of obnoxious, buffoon you see in Adam Sandler movies; her immaturity is not a source for cheap laughs. Instead, she struggles with an insecurity. She is unable to find a fulfilling job, or relate well to her family. Haim’s performance strikes a good balance between outer-strength and inner weakness, making it one that’s not easy to forget.

Best Actor in a Leading Role

Nicholas Cage is known for his melodramatic acting: a skill he couples well with scripts that give him the chance to say absurd things. This formula makes for entertaining performances, but doesn’t always pass the eye-test for “good acting.” Pig, the story of a reclusive chef whose beloved truffle pig is kidnapped, gave Cage the perfect role. A recluse singularly obsessed with a truffle pig sounds like a cartoon character: and indeed the character is eccentric. But Pig’s script creates a context where this eccentricity is sincere and heartbreaking, making it a defining performance in Cage’s already iconic career.

Best Adapted Screenplay

While I’ll admit I haven’t seen the previous Candyman films, I can at least say that I was highly entertained by Nia DaCosta’s 2021 contribution to the series. Candyman is an aesthetically pleasing horror film that both does and doesn’t play to our current cultural-political moment. The film is the story of a diabolical “Candyman” who is rumored to have risen with a vengeance from the pain of his impoverished and over-policed black neighborhood.

What makes the film interesting is that rather than simply relying on the easy political messaging of drawing attention to inequality, it becomes a psychological study of its black main characters. Yahya Abdul-Mateen II stars as Anthony, an artist whose struggle for relevancy, leads him to explore just who the Candyman is, and whether he and the Candyman are meaningfully on the same team. The film presents a nuanced exploration of identity as something that is both chosen by and imposed upon its subjects, and that nuance translates to exactly the kind of suspense a horror film needs.

Best Original Screenplay

Often I go to a film and am awed by the general experience of it, but struggle to retell what I saw after the fact. That’s not the case with Edgar Wright’s Last Night in Soho. While like many auteur-films Wright’s work is partially defined by its aesthetics (Soho celebrates the visuals and (non-Beatles) music of 1960s London), it’s real effectiveness comes from its coherence and unpredictability as a piece of storytelling.

Best Director

Julie Ducournau’s Titane, is the opposite of Last Night in Soho: it’s less a piece of storytelling and more an enticing, shocking spectacle. But the fact that it manages to sew its disparate settings and moods together is a testament to Ducournau’s skill as a director. The film is visually striking, and mixes pulpy horror, with family drama and science fiction. It may be a disturbing pile of nonsense, but Ducournau’s auteurship makes it one of the best films of the year: and perhaps of all time.

Best Picture

Maybe one day the genre of screwball-society-satires will tire on me. Maybe, but not yet. My favorite film of 2018 was Sorry to Bother You, My favorite film of 2019 was Diamantino, and my favorite film of 2021 is Don’t Look Up.

Am I biased because Don’t Look Up was co-conceived by the leftist journalist David Sirota? Absolutely. But that’s in part because Sirota brings a perspective, that liberal Hollywood sorely lacks.

And given how many critics seem to have their own unfortunate biases about the film (lazily describing it is a “Netflix comedy” with an all-star cast, rather than the latest work by a politically-conscious writer-director), I hardly feel a need to apologize for my own.

Don’t Look Up uses its plots twists to show that what we think of as wrong with American politics is only the tip of the iceberg. At the beginning of the film, a trio of scientists (Leonard DiCaprio, Jennifer Lawrence and Rob Morgan) are left hopeless because a Trumpian president (Meryl Streep) refuses to listen to their warnings that an apocalyptic comet is coming. This President, however, turns out to be less Donald Trump and more Kyrsten Sinema. In a shocking turn of events, she decides to listen to the scientists and stop the comet: alas, that is not the end of her story.

Don’t Look Up features lots of interesting little performances. Streep (who apparently did some great improv work on set) is great, as is Jonah Hill as her minion of a son. DiCaprio’s character has all the quirk of a TV nerd (particularly the Big Bang Theory’s Leonard Hofstader), while still coming across as being sincerely portrayed. Mark Rylance steals the show by playing a fusion of Steve Jobs and Elon Musk, while speaking like Jordan Peterson. Timothee Chalamet makes the most of his limited screen time, playing an assertive street kid, with an unconventional affection for Evangelical Christianity. And Melanie Lynskey, playing a relatively mild mannered character, nonetheless brings humanity to a script, that’s just as much about coping with misery, as it is about trying to defeats its causes.

A weird combination of clever jokes and unsettling tragedy, Don’t Look Up makes for a unique and poignant viewing experience. It may not be the kind of thing to win over conservative (and by conservative I mean blasé-liberal) academy voters, but it should serve as a model of political satire and comedic world-building for years to come.

Oscar season has seen the spotlight shone on two “revenge of the underclass” films:

Oscar season has seen the spotlight shone on two “revenge of the underclass” films: If you’re not Mexican and you didn’t do your research you’ll probably not know what “

If you’re not Mexican and you didn’t do your research you’ll probably not know what “ Call me cynical, but my guess is that Vice is one of this year’s nominees for best picture because it’s about a popular news/historical topic and came out at the right time of year. That’s what I think, and I don’t think that’s a radical statement. That said, that is the most cynical thing you’ll read in this review. Vice may me unsubtle Oscar Bait, but given the overall thrill it was to watch I suspect it will hold up as one of the better works from that tradition.

Call me cynical, but my guess is that Vice is one of this year’s nominees for best picture because it’s about a popular news/historical topic and came out at the right time of year. That’s what I think, and I don’t think that’s a radical statement. That said, that is the most cynical thing you’ll read in this review. Vice may me unsubtle Oscar Bait, but given the overall thrill it was to watch I suspect it will hold up as one of the better works from that tradition. Barry Jenkins can probably be said to have picked up the reputation of being an “issues” director. His breakout film, Moonlight dealt with homophobia in a poor, black community. This follow-up film deals with the consequences of police racism. But as the title of

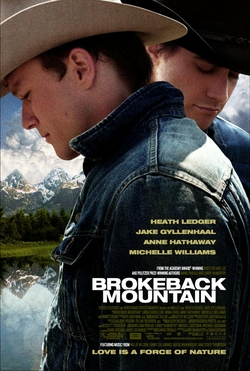

Barry Jenkins can probably be said to have picked up the reputation of being an “issues” director. His breakout film, Moonlight dealt with homophobia in a poor, black community. This follow-up film deals with the consequences of police racism. But as the title of  There are various reasons I take films off the the shelf at the video store or library. Sometimes I systematically try to watch certain works. Other times I go for the oddball covers. In the case of finally seeing Brokeback Mountain, I suppose I was chasing a memory. 2006 was the first year in which I was broadly aware of what films were nominated for the Oscars, even though I was too young to have seen any of them. While my interest was admittedly peaked because a movie about one of my favourite singers (Johnny Cash/Walk the Line) was part of the conversation, I nonetheless retained memories of the names of actors and movies that were not necessarily atop the tabloid world: actors including Brokeback Stars Heath Ledger, Jake Gylenhaal, Michelle Williams and Anne Hathaway,

There are various reasons I take films off the the shelf at the video store or library. Sometimes I systematically try to watch certain works. Other times I go for the oddball covers. In the case of finally seeing Brokeback Mountain, I suppose I was chasing a memory. 2006 was the first year in which I was broadly aware of what films were nominated for the Oscars, even though I was too young to have seen any of them. While my interest was admittedly peaked because a movie about one of my favourite singers (Johnny Cash/Walk the Line) was part of the conversation, I nonetheless retained memories of the names of actors and movies that were not necessarily atop the tabloid world: actors including Brokeback Stars Heath Ledger, Jake Gylenhaal, Michelle Williams and Anne Hathaway, It wasn’t long ago that I would tell you I didn’t watch movies. I didn’t watch TV either. This was not a conscious choice. Rather, I was raised in the kind of household where sitting in front of the TV for unregulated hours was forbidden. By the time I was in middle school I noticed a clear differentiation between myself and my peers. I watched the odd TV show or family movie that my family went to together because it was a good fit for all of us and/or because it was culturally significant (eg Pixar and Harry Potter films). By contrast, my peers were beginning to binge watch live action TV dramas like Lost, Heroes and various crime shows.

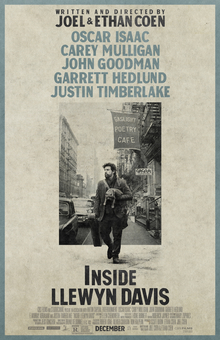

It wasn’t long ago that I would tell you I didn’t watch movies. I didn’t watch TV either. This was not a conscious choice. Rather, I was raised in the kind of household where sitting in front of the TV for unregulated hours was forbidden. By the time I was in middle school I noticed a clear differentiation between myself and my peers. I watched the odd TV show or family movie that my family went to together because it was a good fit for all of us and/or because it was culturally significant (eg Pixar and Harry Potter films). By contrast, my peers were beginning to binge watch live action TV dramas like Lost, Heroes and various crime shows. theatres. This one, Inside Llewyn Davis, attracted me for less mysterious reasons. It was a film about a folk-singer (I like to think of myself as a folk-singer). It was also written/directed by the Coen brothers, who I knew because they’d directed an adaptation of The Odyssey (O Brother Where Art Thou?).

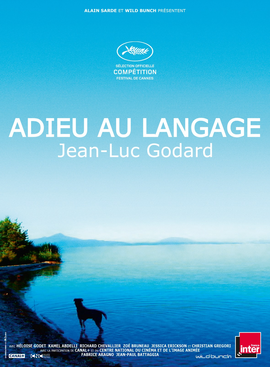

theatres. This one, Inside Llewyn Davis, attracted me for less mysterious reasons. It was a film about a folk-singer (I like to think of myself as a folk-singer). It was also written/directed by the Coen brothers, who I knew because they’d directed an adaptation of The Odyssey (O Brother Where Art Thou?). left me with a strong desire to parody. For me the mindsets of wanting to parody something, and having genuine sense of affection for it are not too far removed from each other. Therefore, when I made a makeshift, imitation Godard film called “La Mort et la Famille” in the summer of 2015 (just under a year and a half since the two titular films of this piece came into my life, and just under two years before I started blogging), it wasn’t just a joke: it was a moment of self discovery. There was (and still is) a lot for me to see, but suddenly I could say it: “I liked movies.”

left me with a strong desire to parody. For me the mindsets of wanting to parody something, and having genuine sense of affection for it are not too far removed from each other. Therefore, when I made a makeshift, imitation Godard film called “La Mort et la Famille” in the summer of 2015 (just under a year and a half since the two titular films of this piece came into my life, and just under two years before I started blogging), it wasn’t just a joke: it was a moment of self discovery. There was (and still is) a lot for me to see, but suddenly I could say it: “I liked movies.”

I was inspired to finally watch Pan’s Labyrinth for two related reasons. Firstly, I was recently introduced to del Toro’s fascination with monsters, insects and fairy tales by a travelling exhibit of his at the Art Gallery of Ontario. Secondly, The Shape of Water recently won the Oscar for best picture and del Toro was named best director. I had mixed feelings about this result. I think del Toro deserved the directorial award due to the beautiful world he created. As a script, I felt The Shape of Water fell a bit short: it made it a tad too obvious who was good and who was evil, depriving it of a necessary dose of complexity.

I was inspired to finally watch Pan’s Labyrinth for two related reasons. Firstly, I was recently introduced to del Toro’s fascination with monsters, insects and fairy tales by a travelling exhibit of his at the Art Gallery of Ontario. Secondly, The Shape of Water recently won the Oscar for best picture and del Toro was named best director. I had mixed feelings about this result. I think del Toro deserved the directorial award due to the beautiful world he created. As a script, I felt The Shape of Water fell a bit short: it made it a tad too obvious who was good and who was evil, depriving it of a necessary dose of complexity. When you see a title as verbose as that of TBOEM (sorry, that’s what I’m to call it), you know you’re in for an unusual viewing experience. TBOEM is the story of Mildred Hayes (Frances McDormand), the mother of a rape-and-murder victim enraged at the failure of police to find her daughter’s assailant. She expresses her rage by renting three abandoned billboards on which she denounces the town’s beloved police chief William Willoughby (Woody Harrelson). The billboards are mundane in their color-scheme and brutally graphic in their words. They are significant in that they come to mean something greater to Mildred than the direct political purpose they serve. That said, the quirk of the film lies not so much in the billboards, as in the conflict they stir.

When you see a title as verbose as that of TBOEM (sorry, that’s what I’m to call it), you know you’re in for an unusual viewing experience. TBOEM is the story of Mildred Hayes (Frances McDormand), the mother of a rape-and-murder victim enraged at the failure of police to find her daughter’s assailant. She expresses her rage by renting three abandoned billboards on which she denounces the town’s beloved police chief William Willoughby (Woody Harrelson). The billboards are mundane in their color-scheme and brutally graphic in their words. They are significant in that they come to mean something greater to Mildred than the direct political purpose they serve. That said, the quirk of the film lies not so much in the billboards, as in the conflict they stir. Coco marks at least two major innovations in the history of Pixar filmmaking. One is that it is Pixar’s first “ethnically” themed film (well there’s Ratatouille and Brave, but it’s Pixar’s first ethnically themed film where insensitive cultural representation was a risk). The other is that it is the first Pixar film to revolve around a child: 12-year-old Miguel (Anthony Gonzalez).

Coco marks at least two major innovations in the history of Pixar filmmaking. One is that it is Pixar’s first “ethnically” themed film (well there’s Ratatouille and Brave, but it’s Pixar’s first ethnically themed film where insensitive cultural representation was a risk). The other is that it is the first Pixar film to revolve around a child: 12-year-old Miguel (Anthony Gonzalez).