Developed by: Noah Pink and Ken Biller

Developed by: Noah Pink and Ken Biller

When I picture Albert Einstein I think of the photograph of him with his tongue stuck out; and I hear him saying that imagination is as important as science. On other occasions, when I hear the phrase “Einstein” I don’t think of a man at all—I just hear a synonym for genius. National Geographic’s recently completed mini-series, Genius,* bridges these two understandings of Einstein, providing audiences with an introduction to who he was, and how he fits into history.

Biopics (or bio-miniseries’) are often not suited for artistic subtlety. They take a real life, a life surely filled with mundanity, and try to condense it down to its triumphs and scandals. Genius is no exception, as it tell the tale of a dynamic 76 year-long life in 10 episodes—episodes featuring multiple suicides, two world wars, the invention of two horrible weapons, and numerous cameos by historical figures (some of which, though entertaining, feel quite forced), in addition to unending family turmoil.

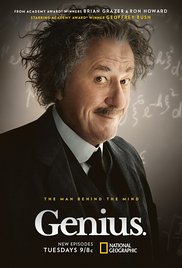

One questionable decision the creators of Genius made was to cast different actors as young (Johnny Flynn) and old (Geoffrey Rush) Einstein. Rush abruptly takes over the role when Einstein is in his 40s, meaning that Einstein suddenly goes from looking like a child amongst his Prussian Academy of Sciences peers to looking a bit older than academy leader Max Planck.

But while this casting choice was not seamless, its non-seamlessness is so obvious that I am inclined to forgive it. If anything the choice to cast two Einsteins should be appreciated as a clever artistic strategy. When one lives with a person, it can be hard to notice changes in their appearance or personality. Such changes become noticeable, however, if one only sees a person occasionally. By making “young Einstein” and “old Einstein” two different roles, Genius insures that we are not de-sensitized to developments in Einstein’s persona (as if we were living with him daily), but rather can see those developments as easily as we can tell the difference between Flynn and Rush.

Much of Flynn’s story line details the struggles of Einstein and his first wife, Mileva Maric (Samantha Colley). Einstein fell for Maric while they were students together, with the two coming to see themselves as part a romantic and academically egalitarian relationship. As circumstances largely beyond Einstein and Maric’s control prevent Maric from pursuing her own physics career, Einstein grows to resent his wife and becomes increasingly misogynistic.

Rush meanwhile plays Einstein after his separation with Maric. Flynn’s Einstein is a realistic character, one whose boyish ambition and obliviousness leads him to make both brilliant and horrible decisions. Rush’s (who is 32 years Flynn’s senior) entrance marks a complete break with Flynn’s boyishness, and an abrupt end to the character’s development. Rush is Einstein as the public knows him—a Dumbledoresque figure: elderly, idealist, and eager to teach to the young and believe in humanity.

Together Flynn and Rush show us multiple ways we can enjoy and learn from history. Rush gives us the comfort of a familiar persona and shows us how we can love him more. Rush’s Einstein emphasizes that math and science are to be enjoyed, and should be enjoyed by all, challenging the stereotype of the cold scientist who arrogantly looks down upon society. He also challenges the notion that scientists should be apolitical, and separate from the world of social justice by speaking out on various causes, making him a target of J. Edgar Hoover’s.

Flynn’s Einstein, however, exposes the downside of lionizing historical giants. Historical icons are disproportionately white and male, meaning their fame can at least partially be attributed to injustice. Flynn’s storyline suggests, for instance, that despite collaborating with Maric, Einstein did not ultimately credit her on their joint papers (perhaps for fear of how society would read it, or perhaps because of his own dismissiveness of her contributions).

Genius is able to accomplish the important objective of criticizing Einstein and promoting the memory of Maric, while still allowing viewers to celebrate the ultimate good (humanitarian and scientific) that came from Einstein’s life. This complex portrayal of Einstein is the result of the distinct contributions of Flynn and Rush. Flynn’s 3D portrayal of Einstein allows us to both see Einstein’s flaws and understand the social conditions that created them. Rush’s more caricatured (though still wonderfully acted) portrayal allows viewers to see what Einstein became, despite the errors of his formative years, and what we can admire about him.

Genius may not be considered revolutionary or artistic television (a possibility that the Einstein story could allow for, given Einstein’s imaginative approaches to solving and explaining physics problems), but it is captivating and educational. Those who wish to know more about the biography of a scientist: what he lived through, how he saw the world, and, to a limited degree, what he discovered, should absolutely consider giving the series a try.

*Genius will have another season, but focus on a different historical figure