Directed by: Xavier Dolan Written by: Dolan and Jacob Tierney

There are parallels between the lives of an up-and-coming child-star and an adult celebrity. This is the premise of 2018’s Vox Lux as well as 2019’s The Death and Life of John F. Donovan. In theory, these films tell two very different stories. Vox Lux looks at two stages in the same person’s life, whereas John F. Donovan is actually about two different people. Both films, however, are united in a struggle. How can you tell the stories of two “different” people at two different ages, while also pitching that those people are quintessentially the same?

There are parallels between the lives of an up-and-coming child-star and an adult celebrity. This is the premise of 2018’s Vox Lux as well as 2019’s The Death and Life of John F. Donovan. In theory, these films tell two very different stories. Vox Lux looks at two stages in the same person’s life, whereas John F. Donovan is actually about two different people. Both films, however, are united in a struggle. How can you tell the stories of two “different” people at two different ages, while also pitching that those people are quintessentially the same?

Vox Lux, though a subtle, indie work, relies on a popular celebrity archetype to gets its message through: that celebrity turns people into cartoonish train-wrecks. In the case of that movie, I was not fully convinced that the mild-mannered-child and brash-adult stars were the same person. Nonetheless Vox Lux’s mainstream assumptions about the consequences of fame made the logical jump coherent enough.

In The Life and Death of John F. Donovan, Xavier Dolan arguably reverses the above formula, contrasting a charismatic child with a soft-spoken adult. The child, Rupert Turner (Jacob Tremblay/Ben Schnetzer as an adult), is being raised by a single mother, Sam (Natalie Portman). Sam has an acting background herself, but the story behind her career as well as that of her ex-partner are somewhat foggy.

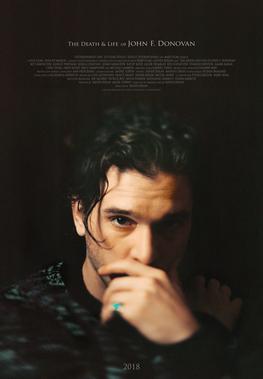

Rupert admires the actor John F. Donovan (Kit Harrington), a choice which appears to be somewhat niche given that Donovan is presented as a not-yet A-List celebrity (he is on the verge of making it as he is about to cast in a superhero film). As a six-year old, Rupert began writing fan mail to Donovan. He got a response, but did not tell his mother. He and Donovan, would then secretly correspond for years.

There’s an almost surreal quality to Rupert’s storyline. His story is set in 2007, but his mother’s hairstyle and his British uniform-school (which aesthetically clashes with his and his mother’s American accents), give the impression that his story is of another age. Furthermore, he and his mother are “actors” yet their lives are presented as entirely mundane. And of course, there’s the fantastic premise that an actor actually diligently responded to a young fan’s letters (and that the young fan’s mother never noticed).

Donovan’s story, meanwhile, it not devoid of this out-of-time surreality. He has a tough, if obscured relationship with his family, led by his mother (Susan Sarandon), who live in a vaguely-vintage, wallpapered world. His overall dynamic, however, is more laid-back than Rupert’s. His scenes are slow, rendering them the main culprit for the film’s low Rotten Tomatoes Score. This is because. Unlike Vox Lox, which posits that unchecked childhood drama gives birth to celebrity firebrands, John F. Donovan argues that for misfits, coming of age, means suppressing what makes one different, even if that suppression is (arguably) more harmful than whatever bullying they would otherwise suffer.

Donovan and Rupert’s stories are both plagued by homophobia. For Rupert, it is an overt force embodied by school bullies, whereas for Donovan, it is an omnipresent spector. The centrality of homophobia to the film further contributes to its chronological-ambiguity. Did Dolan make a mistake in setting his film in the early 2000’s, a time when, yes, casual homophobic slurs and jokes were more common, but at which coming-out would not have been the career-ender that Donovan seemed to fear it was? I suppose the time-ambiguity of the film could have been a subtle-jab at straight viewers, making the same judgement that I am now. Perhaps for a lot of people struggling with homophobia (Xavier Dolan included), the 2000s and the 1950s really didn’t feel as different as some people would be inclined to say they were.

John F. Donovan makes use of the trope of child-who-is-more-emotionally-intelligenty-than-his-elders-and-unsubtley-aware-of-it, as well as low-key Deus Ex Machina figure played by Michael Gambon. Yet if The Life and Death of John F. Donovan has a fatal sin, it’s not its occasional retreats to saccharine cliché, but its general air of subtlety. Dolan and Jacob Tierney’s screenplay tells a story about how we can both deeply-connect-to and not-really-know somebody. They told a story of how people can suffer from social pressures that may or may not be entirely grounded in contemporary reality. Their story was of how subtle things can have a cataclysmic effects. The result was a screenplay that falls in an unfortunate gap between being entertainingly-dramatic and provocatively subtle. The Life and Death of John F. Donovan falls short as a piece of entertainment, but it nonetheless resonates as a poignant meditation on emulation, bigotry and loneliness.

[…] had had very little exposure to Xavier Dolan when I went to see The Death and Life of John F. Donovan earlier this year. I sensed, nonetheless, that something about that film didn’t seem quite right: […]

LikeLike